(Many layers to that title. And warning: not heavily edited because I have homework to do. Expect typos.)

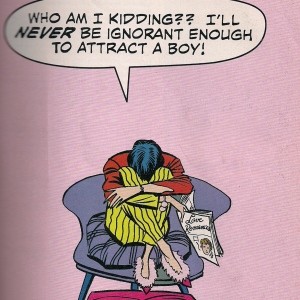

“It’s too feminist. Our audience is men, and men wouldn’t read that. I mean, speaking as a man, I wouldn’t read that.”

When Larbalestier's Liar, which features a black protagonist, was published with a white girl on the cover, the blogosphere raged. But where was the response from Publishers?

I heard it echo across the classroom, seemingly unnoticed by anyone else. We were in Introduction to Publishing, analyzing fake query letters that our classmates wrote for possible acquisition into the mock publishing houses our small groups were supposed to represent. The acquisitions process for a book isn’t common knowledge, so I’ll do my best to briefly explain. Normally, the author writes a query letter to a press, telling a little bit about the book, offering a sense of tone and an idea of the potential market for it. The press then decides whether they want to read more (a process skipped in this classroom exercise,) based on several things. An important two that many people don’t think about is that it’s important for the acquisitions editor/team to think whether a book fits their mission statement and the audience that reads their books. Sometimes a press has to decide that they just can’t do a book justice or that they specialize in other things (for example, maybe they just don’t publish YA or historical fiction.) and can’t take on the project even if they like it or would read it in another circumstance.

But back to the narrative. I don’t know why this classmate’s comment reached my ears in this particular circumstance when I had my own batch of query letters to evaluate and the din in the classroom was enormous. Perhaps I heard it because it seemed so angry and vehement, so contradictory to the typical tone of the class, which is usually a welcoming place full of inquisitive classmates who will be boons to the industry. But, there’s another reason, and I’m pretty sure you’ve thought of it:

Why couldn’t a man read something with a feminist bent? Why did they assume that only men would be buying their books, despite the fact that statistically women buy more books? Also, as this class happened to be 95% female, how could he expect that for this assignment that he would get work that ignored women as potential readers?

I feel bad using this event as a starting point because it might cast the school I’m at in a negative light, so I’m going to say here and now that it was the individual student, not the environment of the program, that caused this statement. But I am going to start here because it’s an excellent launching point to discuss what I’ve come to realize are major anxieties people have concerning publishing in general and big publishing in specific.

Entrenched as I am in publishing school and Ooligan Press projects, I’ve barely had time to think and reflect. Although I do read pretty constantly and have been peripherally aware of the process of preparing a book for market, publishing does feel like a world that keeps to itself, a strange bureaucracy turning and churning, and so now I’m flooded with new information. I’d forgotten to consider that what I was learning was not common knowledge; that my pre-publishing school self, naturally, was not the only one not privy to this information.

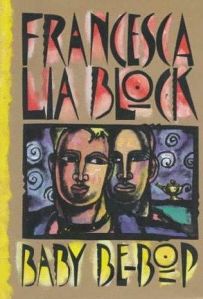

Today, as I started doing research for my final paper on publishing books involving minority groups, inspired by the controversy generated by Bloomsbury Book’s recent whitewashing of Justine Larbalestier’s Liar, which, unbelievably, was followed up last month with their release of Jaclyn Dolamar’s Magic Under Glass, I’ve realized pretty quickly that it’s going to be frustrating and pretty damned near impossible to get inside opinions on what’s gone wrong. I mean, this is nothing new, but why is it still happening? Why is the only commentary I can find Publisher’s Weekly’s rather weak, neutral article and Bloomsbury’s rather transparent plea that they’ve added a new layer of meaning to the book with their cover? Why do I have to go to the author’s blog to find this:

The notion that “black books” don’t sell is pervasive at every level of publishing. Yet I have found few examples of books with a person of colour on the cover that have had the full weight of a publishing house behind them. Until that happens more often we can’t know if it’s true that white people won’t buy books about people of colour. All we can say is that poorly publicised books with “black covers” don’t sell. The same is usually true of poorly publicised books with “white covers.”

Why aren’t there hundreds of publishing blogs saying that this is an example of irresponsible publishing or that the tactic is a one-way ticket to irrelevancy-ville? If I have missed the din, then I apologize. If I have missed a lone blog, I apologize. I’m not saying they don’t exist, but their responses were surely drowned out.

How is it that she, an author with multiple books out, did not know just how common this was without talking to her friends who are publishing insiders? I’m not blaming her; I’m wondering at publishing’s secrecy.

The fact is, people don’t know how books are published. When reading another blog post on the controversy, I was surprised that a book review blogger had to preface her post by saying, “I’ve read/heard repeatedly that authors have little say in the final cover choice” (Reading in Color.) That is, I was surprised that this was not common knowledge. At a Wordstock panel last fall, an audience member asked Karen Cushman how she wrote the summary on the back of her book (I think it was Cushman. It may have been Fletcher.) She looked confused, and then surprised that people thought she wrote her own back cover copy. I know taking these things out of the author’s hands may sound sinister, but coming at this from both a publishing and a writer perspective, I can definitely say that authors sometimes don’t know how to best portray their story’s own strengths–are sometimes far too attached to their work to be able to distill it into an image or a blurb. I mean, I can’t do that for my own work. That is to say, publishers can use their powers over a book for good (though I do think okaying what you’re doing with the author is probably the responsible thing to do.)

Publishing is a funny business. On the one hand, it is a business, and wanting to make enough money to keep the business going and pay your workers a living wages (a near impossibility in an industry that famously, even in established publishing houses, makes a negative profit in the first few months of a book’s release and may never make that money back) is hardly such a bad aspiration. On the other hand, you’re dealing with art and culture, which is heavy stuff, and should be treated as heavy stuff. On a third level (to mix my metaphors,) you also want to entertain. Finding a balance between all this, or at least, making an honest effort to, is responsible publishing.

So now that I’ve had time to reflect, I realize that people assume that Publishing is dominated by that loud voice that I heard in the corner of the classroom. Though my small program, designed with a small to mid-size press focus to make best use of our fantastic Pacific Northwest Publishing hub, is certainly not an accurate microcosm of the publishing world, I have to wonder if perhaps if something similar hasn’t happened at places like Bloomsbury. A voice like that, that speaks so authoritatively and angrily always makes itself sound practical. It waves money around, not considering that there are Black YA readers, for example, that might enjoy seeing a Black woman on the cover or that maybe White YA readers don’t care that much or that there are YA readers who fit into neither of those categories and still might enjoy the book. That there are, in the case of my class’s project, women who read graphic novels who might enjoy reading something with a feminist slant (though I do not know what his definition of feminism is,) or men, or people who fit into neither of those categories. That being responsible and starving don’t always have to go hand in hand.

And yes, it goes without saying, that there’s a more important, higher-cause kind of getting out important bits of culture aspect to this too. I’m just not going into that here because I think most people have heard it, and the so-called voice of practicality doesn’t respond well to it. I just don’t see why we can’t find a way to do both, perhaps making lower profits, but does everything always have to be about making the MOST money?

I don’t know if this voice on the other side of the classroom swayed that group’s decisions or not—I actually suspect the answer is no for reasons that I have no place going into here. But I do think we, as publishers, need to learn to address this voice, which claims to be so worldly, so contrary to any idealistic, bookish, eyes on great Canon sort (which has diversity issues of its own, we often forget. Oh why, oh why is it always one or the other?) who might be left in the publishing industry.

And, finally, why don’t we talk more to readers and writers? Why keep the publishing process a mystery? I mean, not everyone does (in fact, that’s one of Ooligan’s missions. Yay Ooligan! I promise I’ll try not to become like a giant advertisement for my program,) but there needs to be more dialogue—or, I guess, polylogue (I think Bahktin had a term for this that I can’t remember)—between readers, writers, and publishers because we all have a common interest: books and stories.